One notable regret I’ve had from the past few years also came with a lesson. In 2016, my interest in film photography wasn’t just rekindled, it was set ablaze and allowed to become a full-on conflagration. Seeing some part of this, my mother bequeathed to me her mother’s camera: an ancient Argus A2B, manufactured in the 1950s.

Because of the ongoing inferno in my head, I quickly scanned, opened, and scrutinized every part of the camera. This is how I learn. I have to uncover and understand as much as possible on my own before I read the instructions. Within ten seconds, the back was open, and inside was film from God-knows-when, mostly outside of the light-tight canister.

Just like that, I had destroyed the memories preserved on that particular section of celluloid. Great job, Dave. I’m still bothered by thoughts of what some of those photos could have contained. The film canister looked like it was from the 70s. Lesson learned: when handling a new camera, always attempt to rewind before opening the film back.

The Argus A2B is an almost inanimate object. There are no batteries, no real functioning light meter, and the finder is nothing more than a hole with glass in it. The body is comprised of a crude, primitive plastic known as Bakelite. The film is advanced manually by a dial on the left of the camera, which is the opposite of most cameras. The 50mm f/4.5 lens pops out of the camera body, and can only be focused on two zones. If the lens is turned slightly, it is focused to infinity. If it is turned and locked into a groove, it is focused from 6’ to 18’. This design is anything but intuitive, but maybe intuition is what you need to shoot with this thing.

The Argus A2B is an almost inanimate object. There are no batteries, no real functioning light meter, and the finder is nothing more than a hole with glass in it. The body is comprised of a crude, primitive plastic known as Bakelite. The film is advanced manually by a dial on the left of the camera, which is the opposite of most cameras. The 50mm f/4.5 lens pops out of the camera body, and can only be focused on two zones. If the lens is turned slightly, it is focused to infinity. If it is turned and locked into a groove, it is focused from 6’ to 18’. This design is anything but intuitive, but maybe intuition is what you need to shoot with this thing.

I could easily meter with another camera, but I had more fun just guessing what the aperture and shutter speed should be. I have a handy exposure table at the front of my photo memo book, which helps too. You’ll also feel much more confident when you realize that your own eyes make a pretty good light meter. Film is forgiving in this way!

The First Roll, Lomography XPro 200, 2016

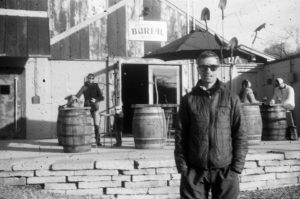

The insatiable fire in me caused me to be reckless, and instead of loading a forgiving black and white or color negative film, I loaded slide film instead for my first roll. The results were mostly poorly exposed, but I absolutely nailed a few of them.

The scans were also littered with dust and particles. I originally thought this might have been the lab’s fault for not cleaning the negatives, but I later learned that it wasn’t that simple.

One thing I love about this camera is the ability to fire the shutter an infinite number of times without ever moving the film. This makes double exposures dead simple to pull off quickly, which makes me more likely to attempt them.

The Second Roll, Kodak Tri-X 400, 2018

In 2018, I want to challenge myself more with film photography. This past January, I picked up the Argus A2B again in an attempt to relieve myself of all automation and to sharpen my adaptation skills. I wanted to prove to myself again that I could take great photos with what almost anyone would consider a “junky” camera. This time, I loaded it with Kodak Tri-X 400, one of the most forgiving films there is, and halfway through the roll, I armed myself with another weapon: a beautiful Minolta Light Meter.

When the scans came back, I was immediately bewildered by all of the dust that had returned. Perhaps this is a distinguishing characteristic of the camera, and not the photo lab? I had used a different lab this time, which led me to do some light research. Turns out, Bakelite naturally attracts dust. This dust is then transferred to the film as it exits the canister and rubs against the inner camera body, and is therefore present on the film at the time of the photograph. This causes the dust to be a permanent part of the photograph. I could certainly clean as much dust from the camera as possible before shutting the back door, but I don’t think I would ever do that. Why?

Because, augmented by the dust and particles, this camera makes images that look authentically old. I love seeing things from 2018 appear on film that looks like it was shot in 1950. Shooting with this camera and film is like creating photographic anachronisms.

I didn’t nail as many exposures as I hoped, but I accept the serendipitous nature of the beast that is film photography without a light meter. Even the shots where I used a light meter are still encumbered by the A2B’s unpredictable focus and framing. That doesn’t matter though. I knew I wasn’t aiming for quality here, and although my photographic tendencies have shifted from the Lomographic carelessness they once were, I’ll definitely keep this one in the stable for those occasional urges.

-Dave

![]()